If you were to say that 80% of the scientists who have ever lived are currently alive, you would be correct, at least as far as the last 300 years are concerned. It was with this assertion that the book “The Half-Life of Facts “ by Samuel Arbesman made me understand something that had been bothering me recently. I am no longer able to follow up on all the articles that interest me. For some years, subscribing to the “feeds” (automatic updates) from the journals of greatest value to my own research resolved this problem. Lately though, not at all.

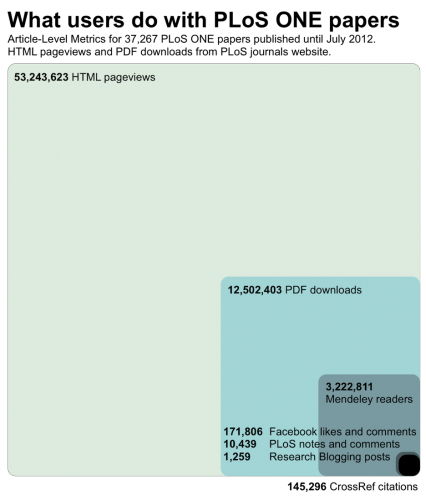

Different uses for the same article. Source: Gobbledygook.

And I am not alone in this deluge of information. As indicated in an article written in 2009 (Renear 2009), with the numbers in it most likely already exceeded – in an era of exponential changes – researchers read more and more articles every year, but give them less and less attention with the finite time available. In other words, the reader’s attention is a commodity which is in increasingly short supply. I must confess that I do not remember the last time I picked up the printed version of a periodical (Honestly, not even any old magazine) and read the material from start to finish. If an article doesn’t grab my attention in the first few paragraphs, at the most, I have some others in the queue which are more promising.

Unless , that is, I know that the content that is there is of interest to me. Just like that book which was not so good at the start, but at the insistence of a friend, I persevered with reading it and was won over, I give much more attention to articles that I know can be more important. I know why someone sent it to me by email. Why one of the researchers that I usually follow on Twitter recommended it. And why a colleague working in the same field posted it on his Facebook page and put my name in a comment.

If people with an interest similar to my own demonstrate an interest in that content, I have much more of a chance of finding something interesting there. And, clearly, in the event that I find something interesting, I am going to pass the recommendation on. It may be by “re – tweeting “ the link, by having fun with the comment, by forwarding the email or by adding the article to Mendeley. This last method will automatically attach yet another reader to the article’s profile in an online network of researchers. Along with the reader, there will be the associated key words and the groups which share the same interests as the person reading.

Each step in this process generates a trail which can be followed – at different levels of proficiency, of course. From the open profile found on Twitter to the closed email system. And each one of them represents a different appeal. Articles which are shared a lot after their publication are those which are of great interest for a particular subject area, whilst those which are cited on Wikipedia will serve as a source to be consulted or have a particular educational value.

These metrics can be extremely valuable. In a real time version of “The Wisdom of Crowds”, a term which is so over – used that it has already lost almost all of its significance , but one which perfectly describes what is happening here – the spontaneous attitude displayed by the users of social networks to share articles is a powerful predictor of their potential informational value. While citations require months or even years to be published and counted, their appearance in social networks can be almost instantaneous, and in certain cases can point to future citations in days (Eysenbach 2011).

As important as the chances of an article being cited by this so coveted metric, are the other types of significance that an article may have. An article can be shared or accessed many times because it has an ideological appeal, without it necessarily receiving future citations. Or it may be used by professors teaching a particular under graduate or post – graduate course, because it brings together relevant information, or good examples. They are all legitimate and important uses for research purposes which can now be outlined followed up and, I hope, enhanced.

It is not by chance that my friend shared the article by Renear and Palmer with me. And, “The Half Life of Facts “was recommended to me on the basis of other users of the virtual bookshop having bought the book after buying a book that I also bought.

References

EYSENBACH, G. Can tweets predict citations? Metrics of social impact based on Twitter and correlation with traditional metrics of scientific impact. Journal of medical Internet research, 2011, vol. 13, nº 4, p. e123. [cited 05 August 2013]. Available from: doi:10.2196/jmir.2012

RENEAR, A. H., and PALMER, C. L. Strategic reading, ontologies, and the future of scientific publishing. Science (New York, N.Y.), 2009, vol. 325, nº 5942, p. 828–32. [cited 05 August 2013]. Available from: doi:10.1126/science.1157784

About Atila Iamarino

About Atila Iamarino

Atila lamarino obtained his Bachelor’s degree in Biology (2006) and his doctorate in Microbiology (2012) from the University of São Paulo. He is currently undertaking his post-doctoral studies there. His expertise is in Genetics, Evolution, General Microbiology and Virology. Since 2007 he has been working in the area of scholarly communication on the Internet with his blog Rainha Vermelha. He is the co-founder of the network of science blogs Scienceblogs Brasil. He is also a consultant to BIREME and SciELO.

Translated from the original in Portuguese by Nicholas Cop Consulting.

Como citar este post [ISO 690/2010]:

Recent Comments