By Jan Velterop

Because it is!

Over the years, most scientific research has become faster. Yet, in areas such as medical and pharmaceutical research, there is always a desire to speed up the process even more, and get results out that help manage and cure diseases, and prevent disability and death. Most researchers, particularly medical researchers, are working as fast as they can, but they have to work carefully and make sure not to jump to conclusion. Premature conclusions could give false promises, but also cause major problems if drugs and procedures that looked promising turn out to have dangerous side effects or not to work as expected in the longer run. The risk of a cure being worse than the disease is real. In the case of the current COVID-19 pandemic that we are facing, the pressure is huge to come up with drugs to treat the disease and a vaccine to prevent its further spread.

Research itself needs the time it takes to do it responsibly and thoroughly, but once there are solid results, the communication of those to fellow scientists can, and should be, faster. Speed is of the essence in order to get the most out of the collective efforts of the scientific community. Any delay in communicating research results is a delay in finding solutions. Unnecessary delays are devastating in cases of life and death.

The benefits of open access, particularly to research where urgency and speed are so important, are obvious. Unfortunately, though, the proportion of new scientific research that is being published with open access is, disappointingly, nowhere near 100 percent yet. In the light of the urgency presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, there are some interesting initiatives to increase the openness of research, data and publications.

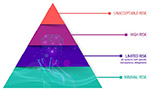

But there is an underlying problem preventing the fast, efficient, and open science communication that is needed, to make the progress that is needed. In English they use the expression “having your cake and eating it”. You cannot. Once you have eaten the cake, you don’t have it anymore. In other words “you cannot have it all”. The stubborn belief that you can is known as “cake-ism”. There is a distinct flavour of cake-ism in the system. Various parties in the area of scientific communication have desires that are difficult to reconcile, or just mutually incompatible. What are those desires? On the part of researchers we generally have: the wish to publish quickly; to having their papers peer-reviewed; to be published in a prestigious journal; to be cited widely and often; to have unlimited access to papers of other researchers; to face little or no cost for publishing with open access; to get recognition for their published work when assessed for promotion, tenure, invitations to conferences, and the like. Individual researchers may have more desires, even.

Many of these desires are shared by funders of scientific research, too. They want their grantees to do well and the work they do to have an impact on science and society, and so enhance the reputation of the funding body and the satisfaction that brings.

Publishers have different desires. They want to generate income from the role they play in the system. That is true for “for-profit” publishers, but in most cases also for “not-for-profit” society publishers, who spend the – often generous – surpluses from their publishing activities on other pursuits their societies deem appropriate for their mission. Some publishers make very generous profits, and would like to maintain those. Others make relatively modest profits, and need to maintain those in order to survive. The general impression is a staggeringly high profitability in the scientific publishing industry, but to be fair, that impression is based primarily on a relatively small number of large publishers. Those publishers publish the majority of scientific papers, though. A quote from the article in The Guardian I referred to just now: “Back in 1988, Maxwell predicted that in the future there would only be a handful of immensely powerful publishing companies left, and that they would ply their trade in an electronic age with no printing costs, leading to almost ‘pure profit’”. That sounds a lot like the world we live in now.”

Ambitious initiatives to make open access to scientific research results the norm, still try to reconcile the conflicting desires of the different players in the field of scientific communication. They try to spare the goat and the cabbage, to use yet another saying that illustrates the difficulty of such an effort. Take, for example, “Plan S”. In spite of the Plan’s admirable aims, and its insistence on transparency of publishers’ costs and fees, it fundamentally accepts that existing publishers, including the large for-profit ones, are essential cogs in the machine. Competition on price does not seem to play an important role and the focus on the selectivity and the prestige, of journals (often conflated with quality) – instead of the quality of individual articles or of the peer-review processes – remains intact. Necessary publishers’ services (e.g., triaging, peer review, editorial work, copy editing) will be defined “in partnership with publisher representatives” and the publishers will be asked to price those. The result is likely an affirmation of the idea that the current financial burden of publishing on the scientific community is reasonable. And, as has been pointed out by Björn Brembs, “If APCs [Article Processing Charges] become predictors of selectivity because selectivity is expensive, nobody will want to publish in a journal without or with low APCs, as this will carry the stigma of not being able to get published in the expensive/selective journals”.

The cabbage – minimal cost of scientific communication – is sacrificed.

Securing the role and comfortable financial position of the large publishers can also be seen in the German “Project DEAL”, a “publish and read” model whereby institutions pay a given publisher a single annual fee to cover access to their journals and APC fees for open access articles published by researchers at the institution in question.

In the context of the European Union Horizon 2020 programme, the EU has issued a tender for a “European Commission Open Research Publishing Platform”. On 20 March 2020 the contract was awarded to F1000 Research Ltd, which has been taken over by the large publisher Taylor & Francis (part of Informa plc) early this year. This is seen as a missed opportunity, as open access advocate of the first hour Peter Suber tweeted, and it is by many others, too. Jean-Sebastien Caux, founder of scipost.org, pointed out the flaw in the criteria for tendering on Twitter: “Criterion F1 for first call (2018): need to have above 1M euro turnover to apply. Criterion F1 for second call: reduced to 500k euro. We don’t have that kind of turnover at scipost.com; that’s kind of the *whole point* of our business model”.

The trouble is that the powers that could drastically reform science communication, are too timid. They do not dare to upset the apple cart of the traditional publishing system. They stick to a frame of mind of cake-ism. Whereas drastic reforms are not unrealistic. Preprints, for instance, could play a crucial role in the separation of communication of research results (speed, efficiency, openness), and assessment (peer review). It won’t be easy to reform the system, to be sure, but tough choices must be made. Slightly modifying the status quo, as seems to happen now, is not enough.

Will global emergencies such as COVID-19 and climate change serve as a wake-up call?

References

Accelerating the transition to full and immediate Open Access to scientific publications: The Plan S Principles [online]. nwo.nl [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://www.nwo.nl/binaries/content/documents/nwo-en/common/documentation/application/nwo/policy/open-science/2019-05_plans_principles_and_implementation/PlanS_Principles_and_Implementation_310519.pdf

Accelerating the transition to full and immediate Open Access to scientific publications: Rationale for the Revisions Made to the Plan S Principles and Implementation Guidance [online]. nwo.nl [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://www.nwo.nl/binaries/content/documents/nwo-en/common/documentation/application/nwo/policy/open-science/2019-05_plan_s_rationale/PlanS_Rationale_310519.pdf

BREMBS, B. What Happens To Publishers That Don’t Maximize Their Profit? [online]. Björn Brembs Blog, 2015 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: http://bjoern.brembs.net/2015/06/what-happens-to-publishers-that-dont-maximize-their-profit/

BURANYI, S. Is the staggeringly profitable business of scientific publishing bad for science? [online]. The Guardian. 2017 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jun/27/profitable-business-scientific-publishing-bad-for-science

CAUX, J.S. [social network]. In: @jscaux [online]. Twitter, March 20, 2020 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://twitter.com/jscaux/status/1241112122718851073

European Union eTendering, Call for tenders from the European Institutions [online]. eTendering. 2019 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://etendering.ted.europa.eu/cft/cft-display.html?cftId=5034

IMADISCH, I. The Pace of Scientific Research Is Picking Up [online]. Harvard Business Review. 2015 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://hbr.org/2015/08/the-pace-of-scientific-research-is-picking-up

Open Access to COVID-19 and related research [online]. open access.nl. 2020 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from:https://www.openaccess.nl/en/open-access-to-covid-19-and-related-research

Project DEAL [online]. Wikipedia [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_DEAL

Services – 134703-2020 [online]. TED Tenders Electronic Daily. 2020 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://ted.europa.eu/udl?uri=TED:NOTICE:134703-2020:TEXT:EN:HTML

SUBER, P. [social network]. In: @petersuber [online]. Twitter, March 20, 2020 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://twitter.com/petersuber/status/1241106911950495746

TRACZ, V. F1000 Research joins Taylor & Francis Group [online]. F1000 blog, 2020 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://blog.f1000.com/2020/01/10/f1000research-joins-taylor-francis-group/

VELTEROP, J. Communication and peer review should be universally separated [online]. SciELO in Perspective, 2018 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://blog.scielo.org/en/2018/05/25/communication-and-peer-review-should-be-universally-separated/

What is Horizon 2020? [online]. Horizon 2020 [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/what-horizon-2020

Wolf, goat and cabbage problem [online]. Wikipedia [viewed 27 March 2020]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolf,_goat_and_cabbage_problem

About Jan Velterop

Jan Velterop (1949), marine geophysicist who became a science publisher in the mid-1970s. He started his publishing career at Elsevier in Amsterdam. in 1990 he became director of a Dutch newspaper, but returned to international science publishing in 1993 at Academic Press in London, where he developed the first country-wide deal that gave electronic access to all AP journals to all institutes of higher education in the United Kingdom (later known as the BigDeal). He next joined Nature as director, but moved quickly on to help get BioMed Central off the ground. He participated in the Budapest Open Access Initiative. In 2005 he joined Springer, based in the UK as Director of Open Access. In 2008 he left to help further develop semantic approaches to accelerate scientific discovery. He is an active advocate of BOAI-compliant open access and of the use of microattribution, the hallmark of so-called “nanopublications”. He published several articles on both topics.

Como citar este post [ISO 690/2010]:

I think there are circumstances where you can have your cake and eat it. The condition is a regular supply of cake. In my opinion that is exactly what happens here. Perennially, governments worldwide are paying billions and billions for research. The costs of publishing the results are a fraction of these huge amounts, often assessed at about 1,5%. The main portion of this money goes to a few powerful publishers and a serious cost reduction can only be achieved by opposing these moguls. Isolated attempts by some libraries, however, have been to no avail. The same amounts that were payed in the subscription era, were payed during the Big Deal period and are now payed for the Transformative Agreements, with an annual increase of 3% to 5%. And profits remained abundant as ever.

So, academia should try harder. Apparently, they are not prepared to do so. And why should they? As long as the cake is supplied in enough quantities every party can have it their way. Academia gets open access, publishers maintain their revenues, and the tax payer pays. This is the basis for Project DEAL and for Plan S.

Yet, I think there is light at the end of the tunnel. Via initiatives like Project DEAL and Plan S, open access will become the default publishing model. Contrary to the subscription model, this model allows for competition. Then a decent market place for publishing may emerge.